Memoirs by Women

Dear blog, it has been a while. In between paid reviews and my day job, I can manage to squeeze in reading time just for me, but it's not so easy to squeeze in writing about it. Lately, I’ve been doing a lot of listening to books via Audible. I’ve found nonfiction and memoirs, in particular, work the best for my attention span on the bus and while doing things around the house.

And knowing my taste, of course all of them are by women.

Shrill: Notes from a Loud Woman by Lindy West

I’ve been a fan of West’s since discovering her writing on Jezebel, and then following her to Twitter. She’s always been an articulate, hilarious, and engaging writer—and she’s from Seattle! In her memoir, Shrill, her voice has room to shine. She fills the pages with essays about her childhood and changing relationship with her body, how entering the world of comedy shook her former love of the genre, her relationship with her late father and his passing, and much, much more. Of course, her dealings with internet trolls are detailed as well, and how she handles them affirms her status as a steadfast fighter for women’s rights. West’s vulnerability pulls you in, makes you want to take stand with her in spite of the trolls lurking behind screens. I look forward to continuing to follow her work online and hopefully, in more books to come.

Sex Object: A Memoir by Jessica Valenti

I found Valenti through Twitter and instantly latched on to her writing on feminism. Her memoir, Sex Object, presents the stark reality of being a woman in the world, starting at an uncomfortably young age. Her story zigzags along her timeline, giving the book a frenetic pace that never lets up. It’s less of a linear portrait of a life and more of a big picture look at the exhausting, insidious threads sexism winds around her from girlhood to womanhood. She covers dating and the confusing power of her sexuality as a teenager all the way up to motherhood. The final part of the book lists real examples of Internet harassment Valenti’s received, and a sinking realization sets in that you’re becoming resigned to such grotesquery, maybe even dulled to it. But it stuck with me, and I started reprocessing similar life experiences with a new perspective. Valenti’s book gave me the power to frame sexism as sexism—and not my fault.

Year of Yes: How to Dance it Out, Stand in the Sun and Be Your Own Person by Shonda Rhimes

I’ve seen a few seasons of Grey’s Anatomy, but not enough to call myself a huge fan, and I only started watching The Catch after reading this book and falling in love. I’d heard rumblings of how great this memoir was, especially on audio, so I downloaded it. And wow, if this is why her fans follow every show she makes, I completely understand. The woman can write.

Rhimes relates how in spite of her success, she felt deeply unhappy for years. That is until her older sister told her that she “never says yes to anything.” That spurred Rhimes’ 'year of yes'—a year where she said yes to everything, even to saying no when she wouldn’t have in the past. This sent her on a journey that helped her connect more deeply with her children, realize which friends weren’t really friends at all, and finally come to revel in the joy of just fully living as herself. This one is uplifting without being cheesy, and Rhimes has a wonderful reading voice—icing on the cake.

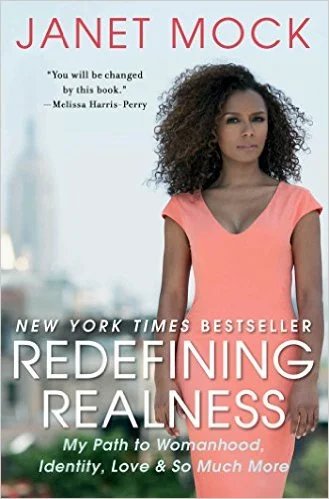

Redefining Realness: My Path to Womanhood, Identity, Love& So Much More by Janet Mock

I’ve been a fan of Mock’s since I discovered her work on an online women’s magazine years ago. As a transgender woman in the spotlight, Mock has always been open and poised. Her memoir is a deep dive into her difficult journey to where she is now, highlighting her childhood in California and Hawaii up to her entrance into college. I often wanted to cry on the bus for the pain she endured, and also for the joy she discovered as she resolved to love herself for exactly who she always knew she was. Her relationship with her best friend Wendi, in particular, was wonderful to hear develop. Wendi really saw Janet from day one, and that carried them both far. I hope Mock writes more about her life in her 20’s, because I will pick that book up the day it drops. And probably listen to it, too. Her voice is incredibly soothing, even as she relates incredibly personal events most wouldn’t be brave enough to tell their own friends.

I’ve got a long wishlist on my Audible account of more memoirs by women that I can’t wait to dive into. That is, when my next credit arrives…it’s really tough to wait when you fly through these things.

Right now I’m listening to Lab Girl, a meditative memoir by Hope Jahren about her life growing into the work of a scientist. I’ll write about that one later.